Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

Joan Miró

,

Joan Miró

20 April 1893

25 December 1983

BIOGRAPHY

Joan Miró was born in Spain in 1893 to a

family of craftsmen. His father, Miguel,

was a watchmaker and goldsmith, while his

grandfathers were cabinetmakers and blacksmiths.

Perhaps in keeping with his family's artistic

trade, Miró exhibited a strong love of drawing

at an early age; according to biographers,

he was not particularly inclined toward academics.

Rather, Miró pursued art-making and studied

landscape and decorative art at the School

of Industrial and Fine Arts (the Llotja)

in Barcelona.

Despite his professed desire to forge a career

in the arts, at the behest of his parents,

Miró attended the School of Commerce from

1907-10. His relatively brief foray into

the business world, characterized by constant

study, instilled a strong sense of order

and a robust work ethic in Miró but at a

very high cost. Following what has been characterized

as a nervous breakdown, Miró abandoned his

business career and subsequently devoted

himself fully to making art.

In 1912, Miró enrolled in an art academy

in Barcelona. The school taught Miró about

modern art movements in Western Europe and

introduced him to contemporary Catalan poets.

Miró was also encouraged to go out into the

countryside in the midst of the landscapes

he wished to paint and to study the artistic

practices of his contemporaries. Between

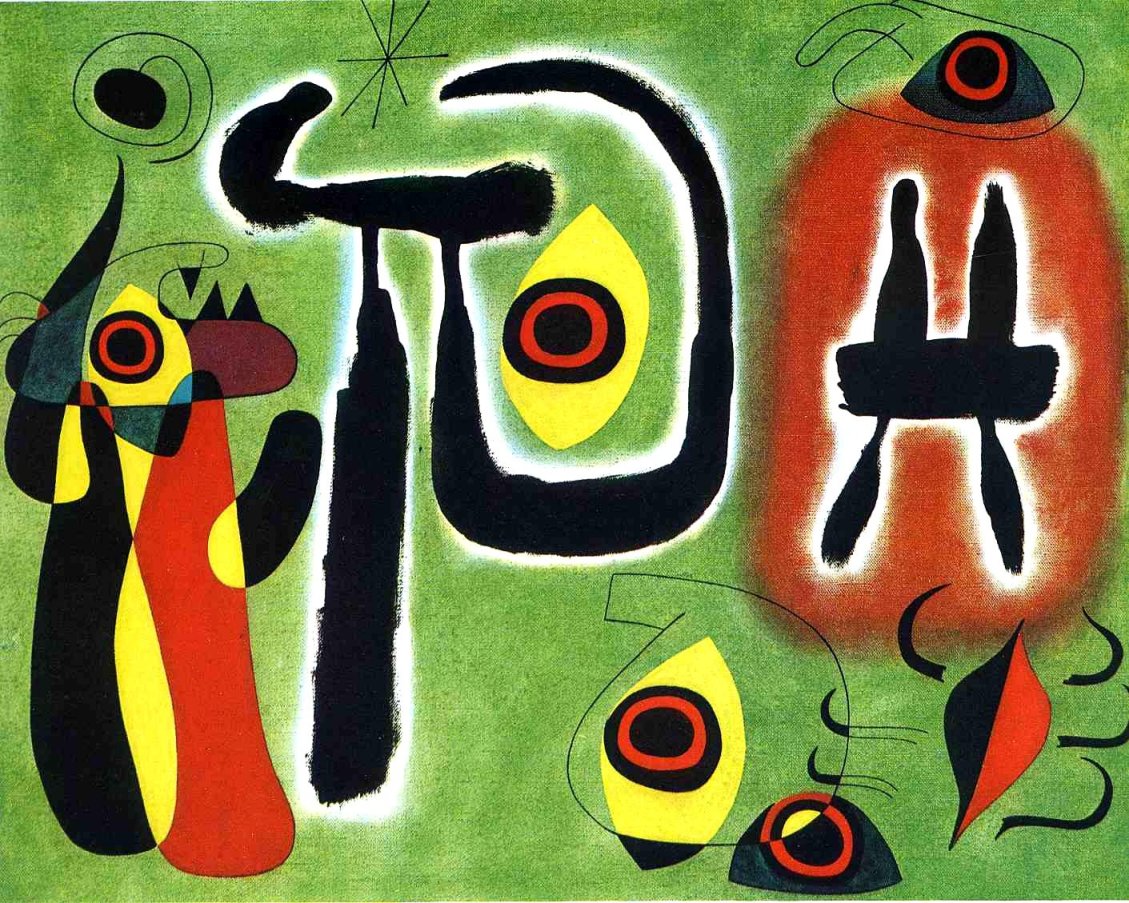

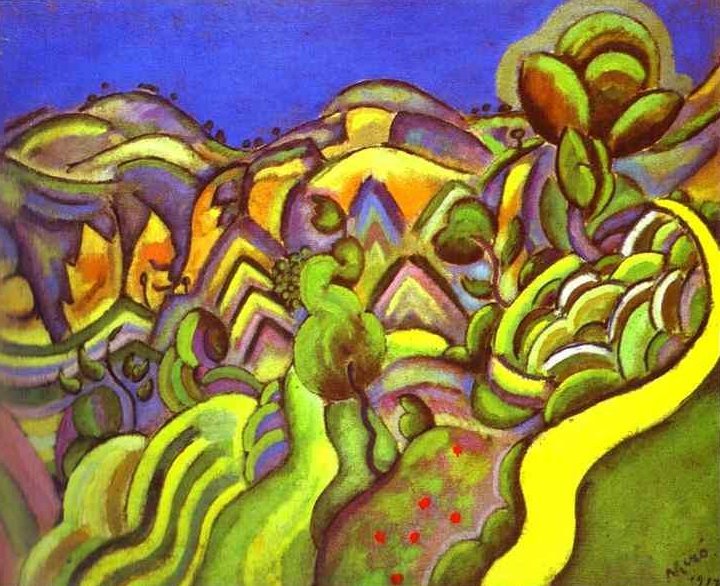

1912 and 1920, Miró painted still-lifes,

nudes, and landscapes. His style during this

period in his early career has been referred

to as "poetic realism." It was

during this phase of his career that Miró

developed an interest in the bold, bright

colors of the French Fauve painters and the

fractured compositions of the Cubists.

In 1919, Miró moved to Paris to continue

his artistic development. Due to considerable

financial hardship, his life in Paris was

difficult at first. When discussing his life

during those first lean, early years in Paris,

the artist quipped, "How did I think

up my drawings and my ideas for painting?

Well, I'd come home to my Paris studio in

Rue Blomet at night, I'd go to bed, and sometimes

I hadn't had any supper." It seems that

physical deprivation enlivened the young

Miró's imagination. "I saw things,"

he explained, "and I jotted them down

in a notebook. I saw shapes on the ceiling..."

Miró was drawn to the Dada and Surrealist

movements. He became friends with the Surrealist

writer André Breton, forming a relationship

that lasted for many years. The Surrealists

were most active in Paris during the 1920s,

having formally joined forces in 1924 with

the publication of their Surrealist Manifesto.

Their members, led by Breton, promoted "pure

psychic automatism," which heavily informed

Miró's work. While the Surrealists experimented

with the irrational in art and writing, Miró's

art manifested these dream-like qualities,

becoming increasingly biomorphic, enigmatic,

and innovative.

To his utter disappointment, Miró's first

solo show in Paris in 1921 was a complete

disaster; he did not sell a single work.

However, a determined Miró went on to participate

in the first Surrealist exhibition in 1925.

He collaborated with the group's members

in the creation of larger commissions, working

with Max Ernst in 1926 on the creation of

Sergei Diaghilev's ballet set designs. In

his own work at the time, Miró painted fantastic

and bizarre interpretations of his dreams.

Miró married Pilar Juncosa in 1929, and their

only child, Dolores, was born in 1931. His

career flourished during this time. In 1934,

Miró's art began to be exhibited in both

France and the United States. He was still

residing in Paris when war broke out in Europe,

and by 1941 Miró was forced to flee to Mallorca

with his family. Perhaps not surprisingly,

warfare and political tension were prominent

themes in his art during this period; his

canvases became increasingly grotesque and

brutal. Concurrently, Miró's first retrospective

was held at the MoMA in New York City to

great acclaim. His renown continued to grow

both in America and Europe, culminating in

a large-scale mural commission in Cincinnati

in 1947. Miró's simplified forms and his

life-long impulse toward experimentation

inspired a generation of American artists,

the Abstract Expressionists, whose emphasis

on non-representational art signaled a major

shift in artistic production in the U.S.

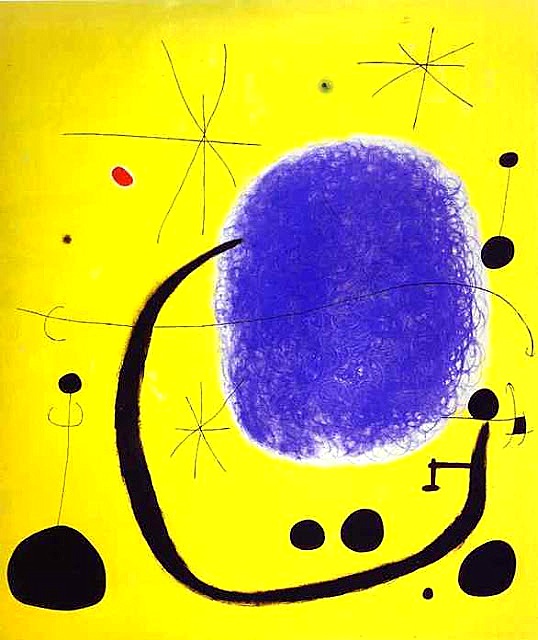

In the 1950s, Miró began dividing his time

between Spain and France. A large exhibition

of 60 of Miró's works was held at the Gallerie

Maeght in Paris and subsequently at the Pierre

Matisse Gallery in New York in 1953. By the

mid-1950s, Miró had begun working on a much

larger scale, both on canvas and in ceramics.

In 1959, Miró along with Salvador Dalí, Enrique

Tabara, and Eugenio Granell participated

in Homage to Surrealism, an exhibition in

Spain organized by André Breton. The 1960s

were a prolific and adventurous time for

Miró as he continued to break away from his

own patterns, in some instances revisiting

and reinterpreting some of his older works.

While he never altered the essence of his

style, his later work is recognized as more

mature, distilled, and refined in terms of

form.

As Miró aged, he continued to receive many

accolades and public commissions. In 1974,

he was commissioned to create a tapestry

for New York's World Trade Center, demonstrating

his achievements as an internationally renowned

artist as well as his place in popular culture.

He received an honorary degree from the University

of Barcelona in 1979. Miró died at his home

in 1983, a year after completing Woman and

Bird, a grand public sculpture for the city

of Barcelona; the work was, in a sense, the

culmination of a prolific career so profoundly

integral to the development of Modern art.

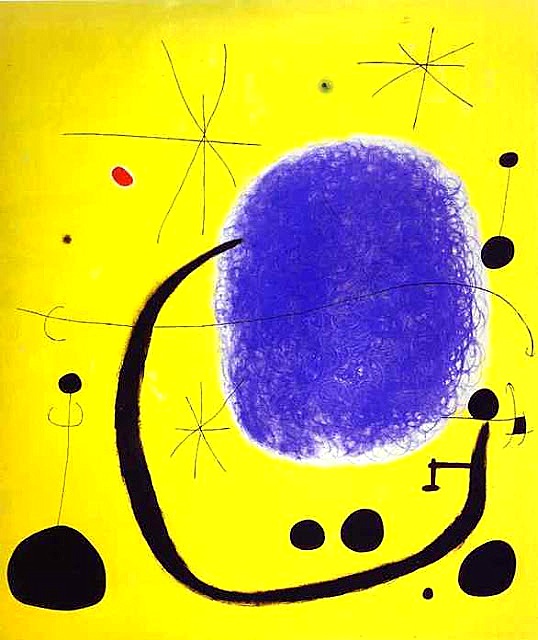

Along with other Dada and Surrealist artists

like Jean Arp and Yves Tanguy, Miró explored

the possibility of creating an entirely new

visual vocabulary for art that, while not

divorced from the objective world, could

exist outside of it. Rather than transitioning

to complete abstraction, Miró's biomorphic

forms remained within the bounds of objectivity.

However, they were forms of pure invention

and were made expressive and imbued with

meaning through their juxtaposition with

other forms and the artist's use of color.

Much has been made of his influence on the

Color Field painters - Robert Motherwell,

Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, and Mark

Rothko, among others; on Alexander Calder,

who was a close friend of Miró; and, more

recently, on designers Paul Rand, Lucienne

Day, and Julian Hatton.

THE SURREALISM

The Surrealist movement began as a literary

group strongly allied to Dada, emerging in

the wake of the collapse of Dada in Paris,

when André Breton's eagerness to bring purpose

to Dada clashed with Tristan Tzara's anti-authoritarianism.

Breton, who is occasionally described as

the 'Pope' of Surrealism, officially founded

the movement in 1924 when he wrote "The

Surrealist Manifesto." However, the

term "surrealism," was first coined

in 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire when he

used it in program notes for the ballet Parade,

written by Pablo Picasso, Leonide Massine,

Jean Cocteau, and Erik Satie.

Around the same time that Breton published

his inaugural manifesto, the group began

publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste,

which was largely focused on writing, but

also included art reproductions by artists

such as de Chirico, Ernst, Arnold Böcklin,

André Masson, and Man Ray. Publication continued

until 1929.

The Bureau for Surrealist Research or Centrale

Surréaliste was also established in Paris

in 1924. This was a loosely affiliated group

of writers and artists who met and conducted

interviews to "gather all the information

possible related to forms that might express

the unconscious activity of the mind."

Headed by Breton, the Bureau created a dual

archive: one that collected dream imagery

and one that collected material related to

social life. At least two people manned the

office each day - one to greet visitors and

the other to write down the observations

and comments of the visitors that then became

part of the archive. In January of 1925,

the Bureau officially published its revolutionary

intent that was signed by 27 people, including

Breton, Ernst, and Masson.

There were two styles or methods that distinguished

Surrealist painting. Artists such as Dalí,

Tanguy, and Magritte painted in a hyper-realistic

style in which objects were depicted in crisp

detail and with the illusion of three-dimensionality,

emphasizing their dream-like quality. The

color in these works was often either saturated

(Dalí) or monochromatic (Tanguy), both choices

conveying a dream state.

Several Surrealists also relied heavily on

automatism or automatic writing as a way

to tap into the unconscious mind. Artists

such as Miró and Ernst used various techniques

to create unlikely and often outlandish imagery

including collage, doodling, frottage, decalcomania,

and grattage. Artists such as Arp also created

collages as stand-alone works.

Hyperrealism and automatism were not mutually

exclusive. Miro, for example, often used

both methods in one work. In either case,

however the subject matter was arrived at

or depicted, it was always bizarre - meant

to disturb and baffle.

THE SURREALISM

IN ARTE EST LIBERTAS

MOVEMENTS-ARTISTS

.jpg)